The result of searching for eternal life

Maha Kumbh Mela is het grootste religieuze feest in het hindoeïsme. ‘Kumbh’ is Sanskriet voor kruik of pot. ‘Mela’ betekent viering en ‘maha’ is groot of uitzonderlijk. CIMIC-medewerker Ashok beschrijft waar het feest voor staat, maar ook hoe de hindoenationalistische politiek de complexe gevolgen van dit Indiase massagebeuren tracht te verdoezelen.

De kosmische verbeelding van de Indiase cultuur is ronduit indrukwekkend. De westerse reiziger staat erbij, kijkt ernaar, wordt overweldigd en begrijpt er meestal niets van. Ofwel is de fascinatie groot en wil je meer weten, ofwel loop je ervan weg.

In elk geval zijn de kosmische verhalen en de psychologische inhoud ervan voor de meeste Indiërs geen ‘metaforen’. Ze beleven ze, identificeren zich ermee, worden er in ondergedompeld en komen er verfrist weer uit. Ware het niet dat de bevolking toeneemt, de heilige rivieren vervuild zijn en er epidemieën kunnen uitbreken.

De gewone Kumbh Mela wordt om de drie jaar gehouden; de ‘halve’ of Ardh Kumbh Mela om de zes jaar in Haridwar of Allahabad; de volledige of Purna Kumbh Mela om de twaalf jaar in Prayagraj (Allahabad), Haridwar, Ujjain en Nashik. Deze vier steden mogen om de twaalf jaar een Kumbh Mela ontvangen.

De grote uitzonderlijke Maha Kumbh Mela vindt maar om de 144 jaar plaats in Prayagraj (in de noordelijke deelstaat Uttar Pradesh) waar de Ganga, Jamuna en de mythologische rivier Saraswati samenvloeien. Een ritueel bad nemen op de plaats van de samenvloeiing van deze rivieren wordt door vele hindoegelovigen beschouwd als de heiligste daad die je kan stellen in je leven.

Dat gebeurde dit jaar dus (2025) van 12 januari tot 26 februari. Die 144 jaar betreft dus een cyclus van 12 keer 12 jaar.

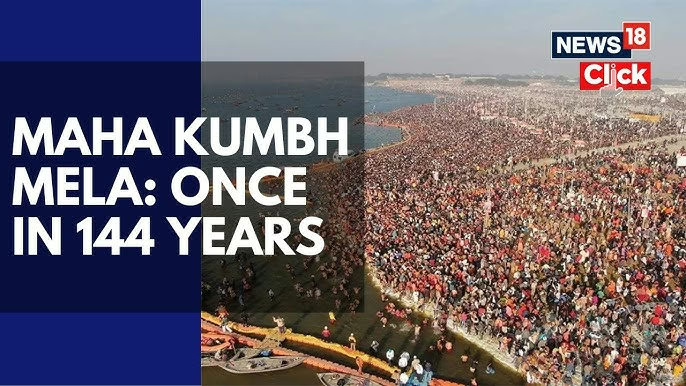

De laatste bedevaart werd in 2013 gehouden (12 jaar geleden) en kende een toeloop van 120 miljoen pelgrims; in 2019 (bij de ‘halve’ Ardh Kumbh Mela zes jaar later) waren er 230 miljoen. Voor de uitzonderlijke Maha Kumbh Mela verwachtte India 400 miljoen pelgrims. Maar de verbeelding begint zijn tol te eisen.

The Maha Kumbh Mela is an event that takes place once every 144 years in India. It is termed the world’s largest gathering, bringing together about 400 million people—nearly 30 percent of the Indian population. The mythical story behind this is that the gods and demons were trying to find eternal life. This could be found in the elixir that had to be churned from a river.

Using the huge mountain called Mandara, mounted on a turtle called Kurma as a churning rod, and a huge snake called Vasuki as a churning rope, they extracted the elixir. Once this was out, Indra’s (the king of gods) son Jayant collected it in a pot and ran away along with Shani (the son of the Sun god), Brihaspati (Jupiter), and the Moon to save it from the demons. He ran for twelve days.

According to the Hindu almanac, a day in the life of the gods is a year in human years. As he ran, drops of the elixir fell in four places on Earth: Prayagraj, Nashik, Ujjain, and Haridwar, on a day when the celestial forces aligned with Jupiter. The pot in which the elixir was taken is called Kumbh in Sanskrit, and mela means celebration.

There are four types of Kumbh Melas: the Kumbh Mela, celebrated every 3 years; the Ardh Kumbh Mela, celebrated every 6 years in Nashik; the Purna Kumbh Mela, celebrated every 12 years; and the Maha Kumbh Mela, celebrated every 144 years.

The twelve-year cycle roughly coincides with Jupiter’s revolution around the Sun.

Millions of Hindu devotees congregate in Prayagraj, believed to be the confluence of three rivers: Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati (a mythological river). Wanting to absolve themselves of all their sins, secure a long and healthy life, and break the cycle of rebirth into a lower being in their next birth, they take a dip in the river.

This year, close to 400 million people flocked to Prayagraj for this ceremony and the festivities. They mostly go to a couple of designated areas to take the dip. The state of Uttar Pradesh made several arrangements to deal with the crowds and regulate them.

Despite all efforts, on 29th January 2025, there was a stampede that killed 30 people. This tragedy was followed by another on 15th February 2025, as people tried to get into trains to reach the holy site. As the crowd grew, train stations were unable to manage them. This resulted in 18 people, including 14 women and 3 children, losing their lives on the platform at Delhi Railway Station. All this happened while the railway police in Delhi were discussing crowd management in their office.

The government of Uttar Pradesh faced strong criticism for prioritizing VIP passes over the security of common people. It appears that hundreds of people received passes to access the ‘ghats’ (places on the river shores) for a holy dip with security and without crowds.

This forced ordinary people to wait for long hours and get caught in stampedes. Though compensation was announced for the deceased, not much is known about the aftermath.

In all this, the role of the media is quite interesting. Mainstream Hindi and English television media, which is usually quick to sensationalize issues, remained silent. They chose not to air critical views or condemn the organizers. In contrast, if this had occurred in an opposition-ruled state, there would have been an outcry for days.

Before tensions could settle, the Pollution Control Board of India released a damning report on the water quality at the site. It stated that the water was not even fit for bathing, as E.coli and fecal matter levels were dangerously high. Samples had been drawn from various parts of the river near the confluence at different times. This could easily have triggered a pandemic of epic proportions.

Again, the report was criticized and rejected by the government. In both incidents, the government denied responsibility rather than addressing concerns, as the issue touched a nerve for Hindu right-wing politicians. They were intolerant not of risks to public safety but of genuine concerns about crowding and epidemics.

The blend of religion and politics is a dangerous combination. Religious rituals are blind to evidence-based inquiry and often condemn or deny the right to question matters of faith. Believers follow what is preached without applying rationale. This is how millions ended up at the holy site.

The objective was not just cleansing sins through a dip; even if they had sinned, reconciliation would be better than an ice-cold dip. Secondly, such gatherings are commercial ventures, involving massive spending and opportunities for small businesses (tea stalls, souvenir shops, etc.). For the government, it is a chance to showcase crowd-management prowess.

In the end, those who sought to extend their lives or wash away sins ended up dying or contracting diseases from polluted water. The irony never seems to end.

Ashok Gladston Xavier

Ashok Gladston Xavier is Associate Professor in Social Work at Loyola College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Lees verder (inhoud februari 2025)