How Eritrean regime agents persecute asylum seekers in Israel

Israeli authorities have long turned a blind eye to the threat Eritreans face from their own government, leaving the community desperate to protect itself, writes Guli Dolev-Hashiloni on the alternative Israeli online 972 Magazine.

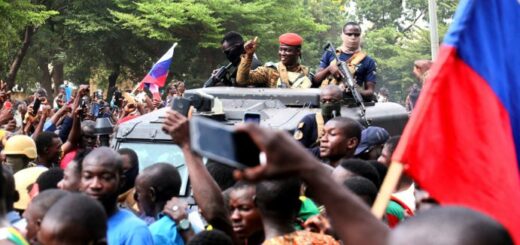

Saturday’s [2 September 2023] riots among the Eritrean asylum seeker community in south Tel Aviv were many years in the making. The incident — in which supporters and opponents of the Eritrean regime clashed at an official Eritrean government event, and drew live ammunition as well as tear gas and shock grenades from Israeli police — prompted opportunistic condemnations from right-wing Israeli politicians.

But the police have long refused to prevent government agents of the Eritrean dictatorship from terrorizing, blackmailing, and sometimes physically attacking asylum seekers in Israel; therefore these protests were, above all, a desperate attempt by the community to protect itself.

The general Israeli public does not know that the Eritrean community in Israel lives under double persecution: on the one hand, by successive right-wing governments in Israel, and on the other, threats by government agents in Eritrea.

Now, when things have spiralled out of control, the Netanyahu government, the most extreme in Israeli history, is once again threatening asylum seekers with deportation — a blatantly undemocratic and illegal move. But the government’s incitement hides the fact that the riots broke out precisely because of the long-standing policy of the Israeli authorities, which protects agents of the Eritrean regime.

In 2019, Amnesty International published a report on the long reach of the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), the ruling and sole legal political party in Eritrea, and the way it extorts refugees who have fled the country. The report focused specifically on Eritrean agents operating in Kenya, but noted that agents are operating out of Eritrean embassies in other countries as well.

Over the past few years alone, embassy agents in Switzerland infiltrated human rights organizations in order to gather intelligence about the local Eritrean community, to threaten them, and possibly also to report false information to the Swiss government about regime opponents, with the aim of preventing them from receiving refugee status.

The Eritrean embassy in South Africa was involved in the suppression of Eritrean student unions in the country, which were critical of the regime. In the Netherlands, supporters of the Eritrean regime have been threatening supporters of the opposition in the country.

There are many more such stories from all over the world. In this respect, at least, Israel is not the exception.

Giving regime agents free rein

In Israel, the agents of the regime blackmail Eritrean asylum seekers in different ways. They prevent refugees from sending money to their families, threaten to confiscate property left behind in Eritrea, refuse to provide regime opponents with consular services at the Eritrean embassy, and threaten those who criticize the Eritrean government on social media that their relatives back home will be thrown into prison.

In extreme cases, regime agents also threaten prominent activists, and even physically attack them.

There are two main reasons for the international persecution led by Isaias Afwerki, the dictator of Eritrea. The first is simple: money. Afwerki extorts money and transfers resources from poor refugees around the world to his impoverished government, via the 2 percent tax it levies on Eritreans living abroad.

The second reason is, of course, political oppression. The persecution is targeted at opposition activists and is intended to prevent them from acting against the dictatorship in Eritrea.

These things are true almost everywhere, but in Israel they are particularly so. Only in Israel do Eritreans live as asylum seekers who, unlike in the rest of the world, are barred from receiving refugee status. For many years now, the Israeli government has refused to examine their asylum applications, thus forcing them to live under a temporary visa, a situation that leaves them restricted and with little protection.

In addition, and unlike the situation across the world, Israel turns a blind eye to the activities of the regime’s agents and allows them to do whatever they want — including public, provocative, and terror-inducing events. Refugee aid organizations and prominent activists in the asylum seeker community had repeatedly warned that a violent clash was expected during Saturday’s event, which was organized by regime agents, yet the police ignored the warnings.

Furthermore, refugee aid organizations have been reporting on the actions of the regime’s agents for years, but the authorities have shown clear indifference.

I myself tried to help N., a dissident of the Eritrean regime who was repeatedly threatened by its agents. They sent him text messages, scared his relatives, and even twice attacked him with knives in south Tel Aviv. I received a text message from the police that the investigation into the matter was closed.

N. lives in constant fear, forced to repeatedly change his phone number, avoid using certain streets, and keep his identity a secret, so as not to expose his family to harm.

In 2020, the Eritrean embassy in Israel reportedly bailed out an Eritrean ‘asylum seeker’ who was arrested during a brawl between regime dissidents and supporters. There is no reason for the Eritrean government to bail out an asylum seeker in the diaspora.

One can assume that the embassy did not release him out of generosity, but because he may have been one of their agents. The Israeli police, the Population and Immigration Authority, and the court that released the man did not find anything strange in this conduct.

The entire Eritrean community in Israel knows where the agents’ headquarters is located. Some of them lived in the same building until recently, which also has a small nightclub at the entrance.

For years, the agents went out there to threaten dissidents, and all the Eritreans I have met knew not to pass by this building on national holidays, when the regime’s supporters wreak havoc in the streets of south Tel Aviv. The police have repeatedly ignored this.

Curiously, the lawyer who represents the regime supporters who participated in Saturday’s clashes also represents the Eritrean embassy.

In other countries with a significant Eritrean refugee community, such as Canada, local governments have banned mass events on behalf of the embassy both for fear that fights may break out, as well as to protect the persecuted community.

In Sweden and Germany, fights broke out after similar events. In Israel, the police received all possible warning signs from the community leaders, and should have known in advance that celebrations by the regime’s supporters would end in disaster. Yet for some reason, they allowed the celebrations to take place.

There are three potential reasons for why Israel allows this situation to persist. The first is that it is afraid to deal with the regime agents, since their imprisonment or deportation will force the government to start genuinely reviewing the asylum applications of other Eritreans living in the country, in order to try and decipher who is an agent and who is not.

This would potentially grant the vast majority of the Eritreans in Israel — the non-agents — a refugee status, which Israel tries to avoid at all costs.

The second is that Israel may have agreements with Eritrea to allow its agents to operate inside its territory. While almost the entire world has imposed sanctions on Eritrea’s totalitarian dictatorship, Israel sells arms to the regime, and thus has economic interests in allowing its emissaries to operate within its borders.

But the actual reason may be more prosaic. Perhaps the police simply do not care about Eritreans attacking each other. And really, why should they care: not only do Eritreans not have status here, they are Black. As long as they do not interfere with the daily life of the Jews in Tel Aviv, fights between Africans are of no interest to anyone.

An uprising by an oppressed community

Eritrea is recognized as one of the cruellest dictatorships in the world. When it comes to freedom of expression, freedom of the press, or freedom of movement, the country has been placed toward the bottom of global indices for years.

Eritrea’s system of forced conscription has prompted researchers to debate whether, legally-speaking, it actually constitutes a system of forced labor, or a system of slavery.

This ‘military service’, which has nothing to do with regular military duties, can be unlimited, such that Eritreans are forced to ‘serve’ the regime for decades without pay and with only a few vacation days a year.

The Eritrean regime uses mass torture, arrests without trial, disappearances, and secret executions. The government is trying to wipe out certain ethnic and religious minority groups, such as the Kunama people and Pentecostal Christians.

The Eritreans in Israel who risked their lives to flee this horror arrived on foot, via a route that passes through Sudan and Egypt, two unsafe countries for African refugees. Israel is the first relatively safe place they have come across. Many of them were tossed into south Tel Aviv by the government upon their arrival.

This weekend’s violent events in Tel Aviv were, first and foremost, an uprising by an oppressed community against its oppressors.

Instead of protecting refugees as required by the 1951 Refugee Convention, the police and the government are allowing the ongoing persecution of Eritreans in Israel. When they rebel against this persecution, the police open fire on them.

The solution to the issue of Eritrean refugees has been clear for years: instead of persecuting the opposition, the state should recognize them as refugees, and those who are agents of a dictatorial totalitarian state, whose sole purpose is to immiserate the lives of actual asylum seekers, should be the ones deported back to their country.

Guli Dolev-Hashiloni

(This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call, 5 September 2023)

Guli Dolev-Hashiloni is a researcher of the Eritrean diaspora in south Tel Aviv.

https://www.972mag.com/eritrean-agents-israel-asylum-seekers/

The long arm of Asmara: riots in Tel Aviv between Eritrean dictatorship supporters and opponents

On Saturday [2 September 2023] there was a full-scale riot in Israel, with groups attacking each other with poles, bricks and anything else they could lay their hands on. The fighting on the streets of Tel Aviv left at least 160 people injured, with eight in a serious condition. Almost 50 police officers were also injured, most suffering from bruises and other injuries caused by stone-throwing.

Yet the clashes had nothing to do with the country’s perennial problems with its Palestinian population or neighbouring Arab states. The violence took place between groups of Eritreans refugees who have fled to Israel. Yet so deep are the differences within the Eritrean exile community that they have been prepared to attack each other – even with firearms.

Riots in Tel Aviv between Eritreans

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reacted by calling for Eritreans involved in the violent clashes to be deported immediately. He went on to spell out what he was calling for.

“Today, at the special ministerial team that I established, we sought several quick measures, including the deportation of 1,000 supporters of the regime who participated in these disturbances. Of course, they have no claim to refugee status. They support this regime. If they support the regime so much, they would do well to return to their country of origin.”

Here lies the clue to what the protest was all about. The Prime Minister was right in pointing to the fact that one faction were Eritrean government supporters, who had no real reason to be seeking asylum in Israel.

The Tel Aviv riot was a pre-planned event between Eritrean government supporters and their opponents among the Eritrean exile community.

Deep divisions in the diaspora

Eritreans who support the government of President Isaias Afwerki – among the most ruthless dictatorships in the world – have been staging a series of what are termed ‘festivals’ across Europe and North Africa all summer. These events are organised by Eritrean embassies in co-operation with local supporters of Eritrea’s sole legal party – the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice, or PFDJ.

They bring together members of the local community to dance, sing and eat Eritrean food. But they are far more than cultural events. They have been held since 1974, when they started in Bologna, Italy. As an Eritrean blogger put it: “For all intents and purposes, Bologna was Eritrea’s second city.”

There were football matches with teams representing the many countries in which the exiles lived: Italy, Germany and Sweden, or else the cities they were resident in: Milan, Florence and Bologna.

Eritreans held the Bologna festival in great affection, but from the start the celebrations had another purpose. They were designed to bind the exile community to the ruling party – a process that was cemented after Eritrean independence in 1993.

With loyalty came a second objective: to raise funds for the fight to be free from Ethiopia and – once this was achieved – to pay for the government programmes initiated by President Isaias.

To do this the president sent his most senior ministers and officials to speak at the events.

In 2014, the fortieth anniversary of the first Bologna festival, the PFDJ held a three-day festival in the city. Key figures from the Eritrean government were invited including Yemane Gebreab, political director of the regime, Yemane Gebremeskel, the director of the Office of the President and Osman Saleh.

Clashes between rival Eritreans

Infuriated that the Eritrean leadership could make their presence felt so directly in a city in which so many exiles had sought sanctuary, members of the opposition confronted the festival organisers directly.

The response was violent, with a pro-government security force, identified as ‘Eriblood’, photographed with their fists in the air, beating up the protesters and driving cars at them.

The groups involved are now more carefully prepared

Since the 2014 protests the pro and anti-government protests have grown in intensity. This year has seen clashes across the globe, from the USA to Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and – last weekend – to Israel.

On the government side ‘Eriblood’ has been replaced by two groups: Eri-Mekhete and 4th Front – both backed by Eritreans who support President Isaias. Mekhete is a Tigrayan word suggesting that you will fight back against anyone who attacks you. The 4th Front is the exile community who are expected to raise funds and discredit the opposition.

Ahead of Saturday’s clashes in Tel Aviv images appeared on social media showing Eritreans pledging their loyalty to Eri-Mekhete and President Isaias.

The challenge was taken up by two movements which brings together opponents of the Eritrean regime. Bright Future (led by Beyene Gerezgiher) mobilises Eritreans who openly challenge the regime, publishing names and contact details of contacts around the world.

The second is Brigade Nehamedu (roughly translates as being ready to fight and sacrifice). This is a more informal grouping which uses social media to organise its supporters. It describes itself as “an Eritrean protest response to the renewed aggressive, hateful and warmongering PFDJ propaganda and fundraiser event[s] billed as “Eritrean Festival[s]”.

Eri-Mekhete

Between these groups supporting and opposing the Eritrean government brought together the hundreds of Eritreans who came out on the streets of Tel Aviv last weekend. The clashes that followed were inevitable.

Ahead of the event the Eritrean democracy movement wrote to the Israeli police, calling for the ‘festival’ to be cancelled “to prevent violence that endangers human life.”

The warning was ignored and the event was held with predictable consequences.

The Eritrean government, stung by the threat to their hold on the Eritrean exile community, and Prime Minister Netanyahu’s remarks, issued a statement declaring that the clashes were “futile acts of subversion – perpetrated through surrogate and rogue groups.” The statement blamed the clashes on foreign intelligence agencies, including the Israeli secret service, Mossad.

The accusation has little credibility. Sufficient anger and frustration have been generated in the Eritrean diaspora to keep these protests and counter-demonstrations on the boil.

As long as the Eritrean government is set on maintaining its ‘festivals’ and young exiles are determined to shut them down, the clashes seem certain to continue.

Martin Plaut

Special for Africa ExPress by Martin Plaut, London, 6 September 2023

Martin Plaut is a journalist and academic specialising in conflicts in Africa, especially the Horn of Africa. He worked as a BBC journalist from 1984 to 2012 and is a member of Chatham House Inst. As of 2019, Plaut was a senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies of the University of London.

The Eritrean ‘Fourth Front’: Festivals as a tool to control the diaspora

Riots broke out in The Hague on 17 February 2024. It is the latest in a string of clashes around the world involving pro-democracy and pro-government Eritreans.

The latter group organises festivals, proclaimed to be cultural festivals, but which pro-democracy Eritreans state are in reality propaganda events; places were high-level Eritrean officials visit, where diaspora Eritreans go under pressure and threats, where military propaganda and hate speech are spread, and where Eritreans have to pay money to the Eritrean government.

Now, a picture is emerging of a highly coordinated effort by the Eritrean government to control the diaspora, which it calls the ‘Fourth Front’, through militia-like structures, including Eri-Blood and Eri-Mekhete.

What is the Fourth Front?

The Fourth Front, abbreviated as 4G, is a military operation with a military command structure, in which there are also a first, second and third front referring to respectively the Western Defense Front, Central Defense Front and Eastern Defense Front, inside Eritrea, responsible for military control in the country; with the Fourth Front being the military defense front outside the country in the diaspora.

This is supported by intelligence, propaganda and financial instruments and all other military capabilities, and falls under the military command structure. Pro-government Eritreans also openly refer to the diaspora’s role in the “fight of Eritrea’s development”as the Fourth Front.

Pro-democracy Eritreans have increasingly linked references to 4G to violent movements and militia, including Eri-Blood, Eri-Mekhete and others. The Fourth Front is to defend the dictatorship of the PFDJ and ensure any challenge to it is taken out at the root.

This view is driven directly by Eritrean President Isaias Afewerki. In a video posted on social media, President Isaias is shown on the national channel Eri-TV. In it, he states that both people inside and outside of Eritrea should be part of Eritrean Defense, and that the campaign abroad should pursue this goal; inside and outside should be viewed as one.

“In the end, one hand has a shovel and another a gun.” This is consistent with President Isaias’s view of the separation between civilians and soldiers. An expert recalls that in a 1998 interview, just before the Eritrean-Ethiopian border war, the President was asked how a nation of 3.2 million could wage war with a nation of 162 million people – and he responded that Eritrea has 3.2 million soldiers.

The modus operandi of achieving this integration of the diaspora is reported to include training of militia which are in some way forced by different means to participate. This can include militia from other ethnic groups. This tactic has been used by Eritrea in regional wars in the Horn of Africa, but is also used in the Fourth Front.

That means that other ethnic groups are involved and receive incentives, training and/or instructions and information that involves them as actors in the operation.

The modus operandi also involves the inclusion of a coordinated disinformation campaign, following the structure as depicted below:

How does it operate the festivals?

The Fourth Front is a tool for the PFDJ to strengthen ‘national identity’ and ‘national consciousness’. The youth wing of the party, Young PFDJ (YPFDJ), often plays a prominent role in the organisation.

Youth from the diaspora, usually born there, frequently receives a VIP welcome when they travel to Eritrea. The latest group of Eritrean youth from London, for example, met with General of the Eritrean Defense Forces, Philipos Woldeyohannes.

One of the youths commented: “I’ll try to share [what I have learned in Eritrea] with refugees who haven’t had the same opportunity as us. We will also try to bring back those who are out of line by telling them the truth.”

In addition, the youth is also expected to fight the PFDJ’s battles online, according to an article on the visit: “The youths discussed in detail with the intellectual youth members of the Eritrean Defense Forces how they can work together to combat false slander against the people and government of Eritrea on social media.”

Festivals are the key tool to translate this vision of the government to the diaspora, to people either loyal to the PFDJ or afraid of it. Although the festivals are portrayed as non-political celebrations, promotions and videos at such festivals show otherwise.

During the war with Tigray, in which Eritrea played a prominent invasive role, the festivals were used to promote war propaganda and hate speech. The festivals are also used to collect funding on top of the 2 percent tax that the diaspora has to pay to the PFDJ, and to check people’s loyalty to the PFDJ. During the festivals, the diaspora is briefed on the message it should spread about Eritrea. In 2023, governors of Eritrea’s regions came from Eritrea to address the diaspora in all kinds of events.

What happened in The Hague?

In another event in The Hague that did not receive as much attention in the media, which took place last November, a proclamation of war was made by the pro-government Eritreans: “Holland is the new Mekelle”. The meaning being: the war in Tigray is over; The Netherlands is the new front.

The actions in The Netherlands were thus announced previously, with the warning that Eritrea wants to have full control over any opposition, comparing the war in The Netherlands with the war that Eritrea fought in Tigray, Ethiopia, which allowed them control over any opposition there to the Eritrean regime.

The ‘New Year’s celebration’ planned in The Hague on 17 February was a well-organised event. The location was kept hidden until the last minute. Pro-democracy Eritreans had been following the event for days to find out how they could warn authorities and organise a protest – but as they did not know the location, this was complicated.

Even as pro-government party-goers were on the bus, only the bus driver was passed a note with the address. The pro-government Eritreans attending the festivals were waving Eritrean flags and wearing shirts with the text “today Sha’ebya, tomorrow Sha’ebya”, in which Sha’ebya is another name for the PFDJ. The party inside was protected by police from the protest going on outside.

Following the events, Dutch parliamentarians asked a range of questions, and called for a thorough investigation into the violence and the long arm of the Eritrean government in the Netherlands. Pro-democracy Eritrean organisations such as Foundation Eritrean Human Rights Defenders condemned the violence and called for peaceful protest.

The 4G disinformation campaign was in full operation following the protests, with pro-PFDJ Eritreans claiming that Ethiopians from Tigray were responsible for the protests, rather than pro-democracy Eritreans. This was strongly condemned by the Tigray community.

Clashes at other festivals

The militaristic attitude of 4G is also visible from festivals in other countries. For example in Tel Aviv, Israel, in September 2023, over 100 people were injured after clashes when ‘blue wave’ protesters clashed with pro-government Eritreans.

Videos appear to show the violence was instigated, as the pro-democracy Eritreans were protesting peacefully. Injuries also occurred in Giessen, Stockholm and other festivals.

Following the clashes in Israel, videos of attacks by regime supporters were circulated on social media. Multiple killings took place. Pictures and videos also circulated showing the Eri-Mekhete militia training ahead of the festival in Tel-Aviv.

Transnational repression and foreign intimidation of diaspora by the PFDJ

Eritrean diaspora and refugee communities have been under surveillance and intimidation by the pro-Eritrean government sympathisers for many years, demonstrating the strength of the long arm of the Eritrean regime far beyond Eritrea.

The phenomenon of targeting the nationals of a country residing abroad by the structures linked to a government apparatus can be summarised under the term transnational repression (or transnational oppression).

Transnational repression refers to the systematic efforts by a government to target and intimidate individuals beyond its borders who are perceived as opponents of the regime. This phenomenon often involves authoritarian regimes employing a range of tactics, including surveillance, harassment, abduction, and even assassination, to silence opponents and maintain control.

These repressive actions extend beyond the borders of the country in question, reaching into diaspora and refugee communities while utilising international networks to track and target individuals deemed as threats to the regime’s stability.

Transnational repression does not only affect diaspora and refugees, but it also poses societal problems to host communities, as well as presenting potential threats to national security and sovereignty of the host country.

The case of Norway

The need to combat transnational repression through adequate legislation and a cross- sectoral approach was identified by Norway in its recent 2023 report by the Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion. The report recognizes that acts of transnational repression can be exercised through violence, physical attacks, threats, harassment and discrediting, infiltration, restriction or conditional consular services, monitoring, and weakening and abuse of international frameworks.

Several examples of Eritrean authorities and/or pro-PFDJ individuals targeting pro-democracy Eritreans were named in the report. That includes infiltration of PFDJ supporters in the diaspora organisations, exclusion, harassment, threatening and ostracising of Eritreans who do not support the PFDJ or who failed to pay 2 percent diaspora income tax.

The riots that erupted in Bergen in September 2023 sparked criticism of the Norwegian government for not acting promptly despite having knowledge of the transnational activities of the PFDJ supporters. An earlier report highlighting the intimidation of Eritrean opposition groups by PFDJ supporters was issued in 2020 by the Norwegian Ministry of Education.

The case of Canada

Transnational repression has been also reviewed in the Canadian context through a paper by the Secure Canada and Human Rights Action Group, using an example of repression by Eritrea.

The report urged the Canadian government to adopt legislative changes, develop policies and increase protection mechanisms for victims of transnational repression. In light of the violence arising from cultural festivals organised by Eritrean pro-government supporters, the Canadian government has been pressed to address transnational activities by the Eritrean government through several petitions.

The case of Sweden

Sweden has been one of the few countries that explicitly identifies the threat posed by foreign states against individuals residing in Sweden in its legal framework. In addition, the Swedish authorities adopted a broader definition of transnational repression by including individuals involved in social or political activism as potential victims of transnational repression, whether they are of Swedish or foreign origin.

Despite that, Sweden has not established any specific procedures laying out accountability for transnational repression acts. Refugees and asylum seekers are often exposed to harassment by the authoritarian regime of the state where they come from.

Establishing refugee status is done under the auspices of the Swedish Migration Agency (SMA) which uses the services of uncertified translators for groups of languages that are not widely spoken.

The Eritrean asylum seekers experienced threats and intimidation from the interpreters contracted by the SMA working on behalf of the PFDJ.

Another example showed that those Eritreans who do not support the PFDJ do not have access to consular services which negatively impacts the refugee status determination process as well as family reunification process.

The case of the Netherlands

In the past, the Dutch government commissioned a report highlighting the foreign influence of the Eritrean regime on Eritrean communities in the Netherlands. Building on that, another commissioned report introduced a comprehensive study comparing the nature and the extent of 2 percent diaspora income tax in seven countries across Europe, namely Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Belgium, Germany, Sweden and UK.

In all of these countries, the “2 Percent Tax is perceived as mandatory by Eritreans in the diaspora and that non-compliance may result in a range of consequences, such as denial of consular services and punishment by association of relatives in Eritrea, including human rights violations”.

In addition, Eritrean regime supporters do not direct their intimidation and repression only towards Eritrean nationals but often also towards those human rights defenders and activists who voice their opinion against the current regime.

Increasingly, the festivals organised by the PFDJ and its supporters are gaining recognition as a tool used in a wider strategy of transnational repression by the PFDJ. Although there is growing awareness of the broader issue of transnational repression, many countries still lack the legislative framework to effectively deal with the threats of issues such as the Eritrean festivals.

EEPA, Brussels, 29 February 2024

Lees verder (inhoud februari 2024)