Thinking about the Sahel (deel 3 en 4)

Het is als een open deur intrappen: de instabiliteit in de hele Sahel, van de Atlantische Oceaan in het westen tot de Rode Zee in het oosten, is de afgelopen maanden alleen maar toegenomen. Vooral Burkina Faso, Mali en Niger dreigen weg te zinken in armoede, geweld en chaos.

De – schaarse – berichtgeving over wat er écht aan de hand is, gaat alle kanten uit. Enerzijds zijn er de vreugdekreten van de ‘neosoevereinisten’ om de herwonnen onafhankelijkheid van de Sahellanden die eindelijk hebben afgerekend met de vermaledijde ex-kolonisator Frankrijk en zijn militaire interventies en neokoloniale belangen, maar anderzijds is de veiligheidssituatie er nog nooit zo slecht geweest met vrijwel dagelijkse aanvallen van jihadistische gewapende groepen, terwijl ook de reguliere legers niet vrijuit gaan bij zware mensenrechtenschendingen.

De samenwerking met de ‘nieuwe militaire partner’ Rusland heeft vooralsnog niet de verhoopte resultaten opgeleverd die de militaire machthebbers voor ogen hadden, integendeel. Van een herstel van een min of meer democratisch bestuur is zelfs helemaal geen sprake meer. De militaire junta’s zijn duidelijk niet van plan om snel te vertrekken, al zou de toenemende ontevredenheid onder de bevolking hen daartoe wel eens kunnen dwingen.

De Nederlandse journalist en West-Afrikakenner, Bram Posthumus, schreef de afgelopen zomer een zeer lezenswaardige zevendelige blog over de Sahel, een regio die hij vanuit zijn jarenlange ervaring als correspondent bijzonder goed kent en waar hij nog vele contacten heeft. Wij brengen zijn bijdragen in vier afleveringen in de CIMIC-Nieuwsbrieven tot december. Hierbij deel drie en vier.

Jan Van Criekinge

Neo-colonial blunders and a democratic deficit – the outro

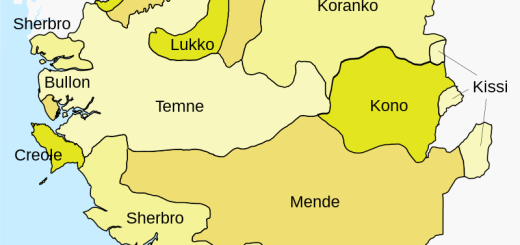

While writing it suddenly occurred to me that it would be nice to show my wonderful readers where the Sahel actually is. I’m a bit slow with these things…

One of the most striking subjects Rémi Carayol (nvdr: zie Nieuwsbrief#55: https://cimic-npo.org/2024/09/26/55-011/) describes – and one that I largely missed, not intimately familiar with the ins and outs of French domestic politics – is the deep democratic deficit that accompanies what is known as ‘Opex’, the overseas operations of the French military, including Opération Barkhane.

This has several aspects: the absence of parliamentary oversight, the (mostly fawning) media coverage and the resultant absence of public debate about these operations.

For instance, French president François Hollande’s announcement that his government was ending three separate military missions on the African continent (Épervier*, Licorne*, Serval*) and was creating Barkhane (annual price tag: one billion euros) was just that: an announcement. No discussion, no scrutiny, no debate – nothing.

(* Épervier, 1986 – 2014, concentrated primarily on protecting Chad against incursions by forces from Colonel Ghadaffi’s Libya, later used as stand-by for other operations, for instance in the Central African Republic;

* Licorne, 2002 – 2015, designed to keep government and rebel forces in Côte d’Ivoire’s political conflict apart, much reduced in size after the end of that conflict in 2011;

* Serval, 2013 – 2014, asked (let’s keep it friendly for now…) to stop the advance of jihadist insurgents in Mali, ended when that objective had been realised).

“It’s a war behind closed doors,” Carayol writes. The French Constitution gives the parliament the right to declare war, but these Opex are not covered by any legal provision. A baffling oversight, which the Executive and the army’s top brass like – very much. Because they can do what they want, far away from home and far away from the public eye.

Here’s an example among many: targeted extrajudicial assassinations. Carayol writes that France, taking after the US example, had a list of ‘High Value Targets’ with seventeen names on it. Who authorised the drafting of that kill list and what were the criteria for putting someone on it? Nobody knows. Was it ever discussed in parliament, let alone in public? Never. Perhaps as many as ten assassinations took place.

Same story with the illegal prison at the Barkhane camp in Gao described earlier. Same story with the armed killer drones Barkhane started using in December 2019. Drones dramatically change the war effort, as they are cheap, lethal and operated from a distance, reducing military casualties.

Excellent subject for debate, one would say, but by the time the French parliament finally got round to discussing their deployment, they were already in use.

Carayol also describes the endless tussles between the diplomatic and military sides of French foreign policy and how diplomats found themselves frequently outmanoeuvred by the intelligence community and the army top brass, often with the explicit political backing of presidents like François Hollande and ministers like the arrogantly tone-deaf Jean-Yves Le Drian.

The latter’s crowning achievement was his transfer – under Hollande’s successor Emmanuel Macron – from the Hôtel de Briennes, where the Minister of Defence resides, to the Quai d’Orsay, home to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, thus even physically confirming the triumph of the generals and spies over the diplomats and mediators.

It confirmed the near-total militarisation of French policy in the Sahel. What also won out in this fashion was the military’s enduring obsession with eradicating terrorism that came to define France’s policies in the Sahel at the expense of everything else.

Here are a few examples, among many:

In Mali, the egregious behaviour of the clan surrounding former president I.B. Keita was considered par for the course. France had no opinion on the fact that the ruling clan had made corruption its SOP, especially after Keita’s (presumably doctored) re-election in 2018.

Chad, nicknamed ‘the desert aircraft carrier’, is home to one of France’s elaborate military installations and so Paris had no opinion whatsoever regarding the coup that placed Déby Junior on the throne after his father was killed in one of Chad’s never-ending battles with yet another rebel group in April 2021.

And in Niger, France was strenuously looking the other way as more or less democratically elected presidents kept on reducing space (never large to begin with) for civil society activism and independent journalism, a practice the junta of General Tchiani that replaced them, has continued and amplified with alacrity.

One irony, then, is that the French military-determined obsession with battling real or presumed terrorists, which superseded everything else including democracy and good governance has been the exact thing that has made fresh coups d’état pretty much a certainty. No amount of feigned indignation will change that.

But the ultimate irony is that this dominance of military analysis aided and abetted by rightwing extremism from the likes of Bernard Lugan has contributed to the establishment of the very strongmen that supposedly can solve problems and get stuff done. Except that they don’t.

Whatever Mali’s Colonel Assimi Goïta, Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traoré and Niger’s General Abdourahamane Tchiani actually do … is done in the service of Vladimir Putin, Europe’s – and France’s – most deadly enemy since the end of the Second World War and one who sits squarely in the same ideological camp as Lugan.

If you think that this look a bit like Algeria’s domestic politics (minus a brutal civil war), you are not wrong. And it’s to Algeria where we’re heading next.

Generals and spies

Algeria has played a complicated and shady key role in the genesis, gestation and expansion of the networks of organised crime and later jihadism in the Sahara and the Sahel.

That, at least, is the view of the writer François Gèze, in a very informative chapter on Algerian neighbourly meddling. It appeared in a book of essays published in 2013 under the title La guerre au Mali. Gèze makes this plausible point: without the Algerian intelligence services and military, the jihadist criminal enterprise in the Sahel would probably not have taken off the way it has.

Algeria sometimes seems to be the blind spot in many of the analyses and commentaries that deal with the arrival of the ‘jihadist’ crime syndicates in Mali, with attention mainly – and understandably – focussed on the disaster NATO created in Libya in 2011.

There, the objective was to assist French president Nicolas Sarkozy in his plan to do a Margaret Thatcher/Falklands/Malvinas on Libya because his domestic political life was getting a little too uncomfortable. The forced removal of the autocrat Muamar Ghadaffi had nothing to do with Libya.

Algeria has been a securocracy since it liberated itself from France in the bloody 1954 – 1962 War of Independence that has caused deep and never addressed traumas on both sides of the Mediterranean Sea.

The war explains why Algeria has been dominated by an all-powerful army and an all-powerful intelligence service; they won that war. The war also explains why the extreme right holds such appeal for the French electorate, much in the same way as the keys to understanding the current Dutch love affair with fascism lie in Indonesia: the end to their racist colonial projects.

The extreme rightwing politician Marine Le Pen has attempted to make the Rassemblement National (the former Front National) look respectable, but history will never forget that her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, the founder of the FN, fought in France’s colonial war in Southeast Asia and as an intelligence officer tortured Algerian freedom fighters and their sympathisers, charges he denies.

When in 1991 the Front Islamique pour le Salut (FIS), a political movement advocating for sharia law in Algeria won national elections, the army stepped in and staged a coup, with French consent. It means that the Algerian securocrats and their French backers, in that order, bear responsibility for the horror that was to follow: a decade of brutal civil war during which seemingly everything was permitted, as long as it was poor and defenseless Algerians that bore the brunt of the blind violence meted out by both sides.

Both the army and the armed and radicalised wing of the FIS, now calling itself GIA (Groupe armée islamique) committed acts of brutality not seen since the 1950s. The army imitated the French practice of committing vile acts against civilians while donning the enemy’s uniform, while GIA committed equally gruesome and indiscriminate killings.

By the time Algeria was finally allowed to start healing from these atrocities, nineteen Saudi terrorists flew two airplanes into the tallest skyscrapers in downtown Manhattan, New York, and another one into the Pentagon, an act that according to François Gèze changed everything. The doomed War on Terror began and everything was permitted – again.

Gèze chronicles how under the guidance of the DRS (Algeria’s omnipotent intelligence service called Département de renseignement et de sécurité) the GIA structures were exported to the neighbours: first to Mauritania with little success except for one attack on the army in 2005 and then to Mali.

During that process the GIA transmogrified into AQMI – Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. This is when we see DRS-guided if not DRS-produced criminals like Mokhtar Belmokhtar (the infamous cigarette smuggler) and Aldelmalek Droukdel (an Islamist mercenary who fought in Afghanistan) rising to prominence and AQMI organising its seed money by kidnapping Europeans, for the release of whom European governments paid large amounts of money.

Coordination for these operations was done, in part, out of Algeria’s giant embassy in Bamako, prompting one taxi driver to shout, as we were passing the not-so-terribly-diplomatic building: “We have a very bad neighbour!”

It is at the very least deeply ironic that France was called to start Opération Serval (Barkhane’s precursor) in January 2013 to deal with the fallout of the extremist nonsense the Algerian generals triggered in 1991 with the tacit approval if not active encouragement of France…

No surprises, then, that the Algeria-brokered 2015 Algiers Peace Accord was only highly reluctantly accepted by the Tuareg rebels and the Malian government and not just because they were signing a text they had hardly contributed to.

I remember standing next to Malian friends in the Malian capital Bamako, June 2015, as we watched national television coverage of the supposedly solemn signing of the accord. The friends were watching the faces and the body language of the high-ranking fighters signing the document in Algiers and commenting: “They’re not serious about this.”

Eight years later, Colonel Assimi Goïta’s junta killed the whole thing, as it recaptured the rebel headquarters of Kidal, its only and easiest victory. Nobody mourned the end of the ‘Algiers Process’ and relations between Mali and its northern neighbour remain as dreadful as they have always been.

The capture of Kidal was followed by the entirely predictable spate of terrible exactions (mass murders, rapes, tortures, lootings) of the people in that region by the Malian army, ‘assisted’ by the specialists in brutalising civilian populations, the Russian Wagner mercenaries, now re-branded Africa Corps. More about them shortly.

Bram Posthumus

De eerste twee delen van Bram Posthumus’ blog ‘Thinking about the Sahel’ verschenen in Nieuwsbrief#55 van september: https://cimic-npo.org/2024/09/26/55-011/

Lees ook:

- Sahel: het Franse leger heeft zich hopeloos vastgereden in het zand van Mali https://cimic-npo.org/2021/03/23/sahel-het-franse-leger-heeft-zich-hopeloos-vastgereden-in-het-zand-van-mali/

- Elections in Mali and Burkina Faso postponed for forever (and a day) https://cimic-npo.org/2024/06/30/54-008/

- Waarom al die staatsgrepen? https://cimic-npo.org/2023/11/23/47-011/

- Should Military Leaders be Barred from Addressing the UN? https://cimic-npo.org/2023/10/23/46-011/

- Militairen aan de macht in de Sahel: de puinhoop wordt alleen maar groter https://cimic-npo.org/2023/02/26/40-001/

- Zoveelste staatsgreep in West-Afrika duidt op regio in diepe crisis https://cimic-npo.org/2022/01/28/item29-010-2/

- Dood Tsjadische president Idriss Déby stelt Franse belangen in de regio op scherp https://cimic-npo.org/2021/04/23/dood-tsjadische-president-idriss-deby-stelt-franse-belangen-in-de-regio-op-scherp/

- Algerije -Frankrijk: “Verontschuldigingen alleen zullen niet volstaan”, zegt historicus Benjamin Stora https://cimic-npo.org/2021/06/26/item24-013/

Lees verder (inhoud oktober 2024)